I’ve already said that we spent hours and hours in the trees, and not for utilitarian reasons, like many boys, who climb up just to look for fruit or birds’ nests, but for the pleasure of overcoming difficult protuberances and forks, and getting as high as possible.

Batree Serif

Type Design

Batree is a serif text typeface I designed based on the Baron in the Trees, a philosophical fiction written by Italo Calvino in 1957.

The book is themed on independence, rebellion, and a full self. Its protagonist, Cosimo, is a young baron who climbs up a tree after a dispute with his father and never came down for his entire life as he promised.

The book is themed on independence, rebellion, and a full self. Its protagonist, Cosimo, is a young baron who climbs up a tree after a dispute with his father and never came down for his entire life as he promised.

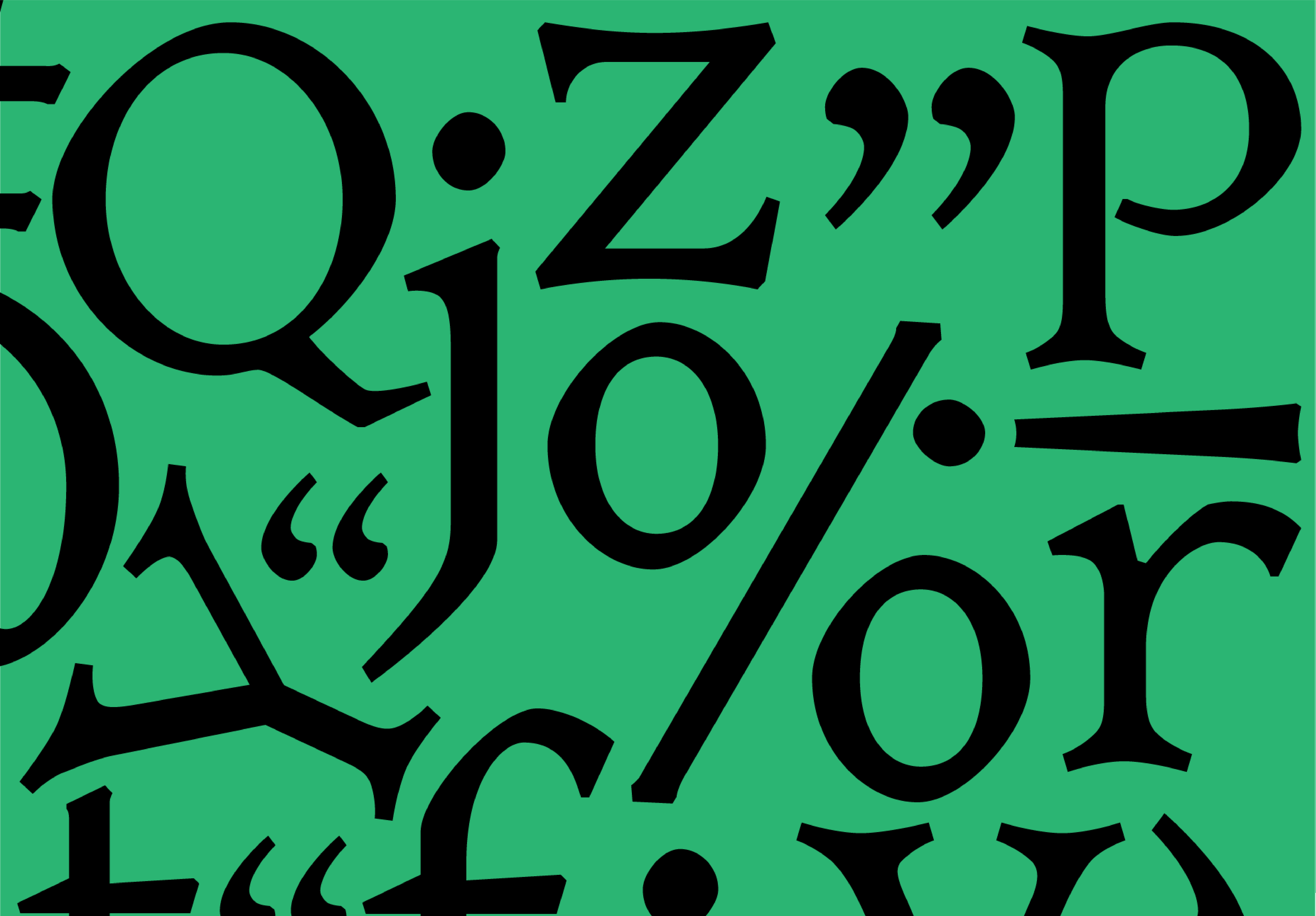

Trees, the long-tailed tit, and the French sword Cosimo always carries around are three key imageries I extracted from the novel, which I think represent the protagonist’s personality, to design the typeface.

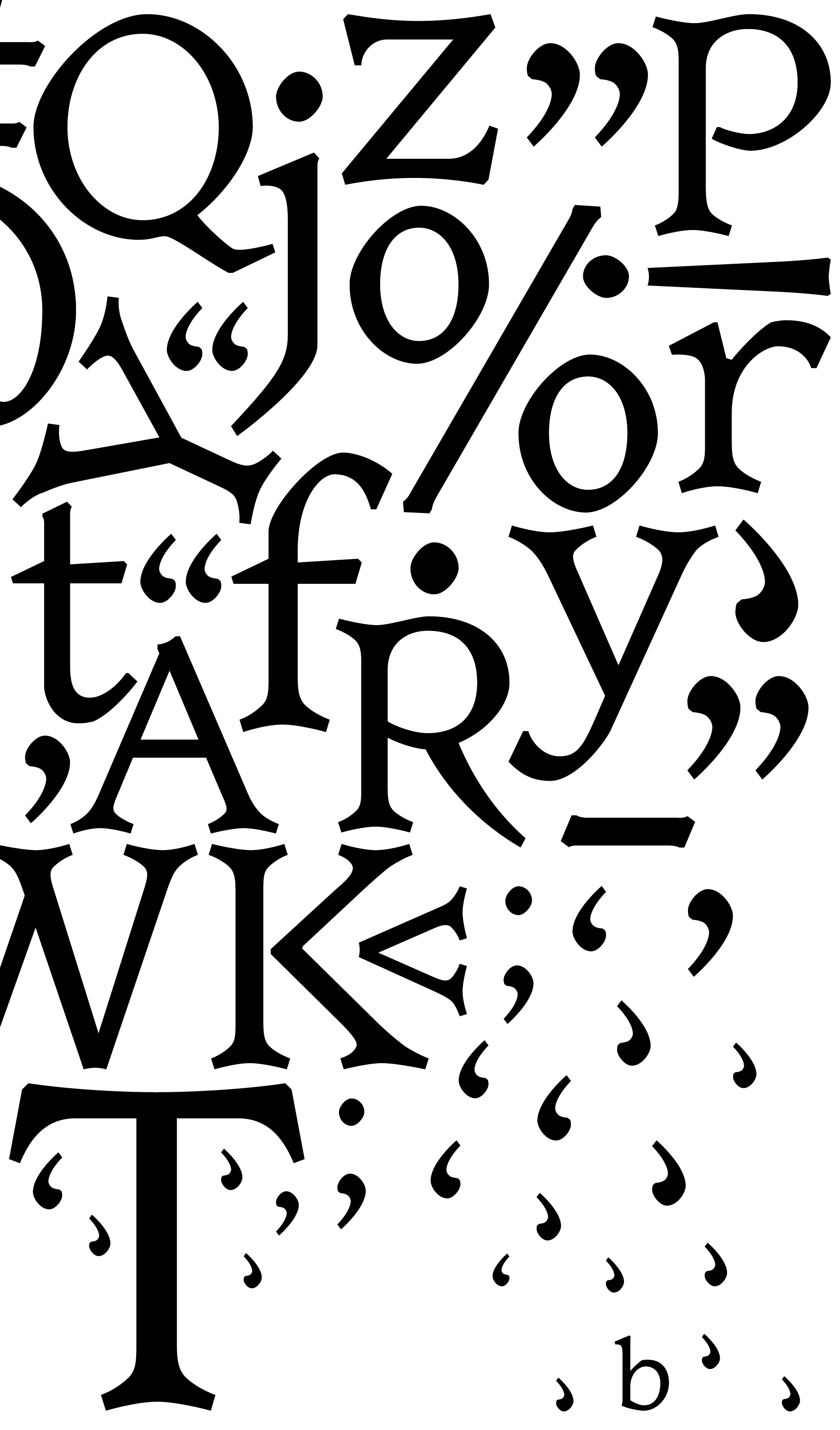

The typeface is playful, jumpy, disobedient as well as robust and determined. It features a tall x-height and generous counter space to give the letters an airy feeling and strong legibility at a small size. Dynamic asymmetry and detailed variations can be seen in each letter. The curved and light-footed serifs draw inspiration from both tree roots and the feet of tits to emphasize the idea of “never touching the ground.” A combination of angular cuts and smooth curves is shown in each character and exaggerated in lower cases.

The typeface is playful, jumpy, disobedient as well as robust and determined. It features a tall x-height and generous counter space to give the letters an airy feeling and strong legibility at a small size. Dynamic asymmetry and detailed variations can be seen in each letter. The curved and light-footed serifs draw inspiration from both tree roots and the feet of tits to emphasize the idea of “never touching the ground.” A combination of angular cuts and smooth curves is shown in each character and exaggerated in lower cases.

36pt

28pt

Ombrosa is no longer there. Looking at the empty sky, I wonder if it really existed. That ornamentation of branches and leaves, forks, lobes, feathers, minute and without end, and the sky appearing only in irregular flashes and cutouts, maybe existed only because my brother passed there with the light step of a long-tailed tit, was an embroidery, made on nothing, that resembles this thread of ink.

18pt

13pt

I’ve already said that we spent hours and hours in the trees, and not for utilitarian reasons, like many boys, who climb up just to look for fruit or birds’ nests, but for the pleasure of overcoming difficult protuberances and forks, and getting as high as possible, and finding beautiful places to stop and look at the world below, to make jokes and shout at those who passed under us. So I found it natural that Cosimo’s first thought at that unjust anger against him was to climb the holm oak, a tree familiar to us, which, spreading its branches at the height of the dining-room windows, imposed his contemptuous and insulted behavior on the sight of the whole family. Cosimo climbed up to the fork of a large branch where he could sit comfortably, and there he sat, legs dangling, arms crossed, with his hands in his armpits, his head pulled down between his shoulders, the hat low on his forehead. Our father leaned out the window. “When you’re tired of sitting there you’ll change your mind!” he shouted. “I’ll never change my mind,” said my brother from the branch. “I’ll show you, as soon as you come down!”

Cosimo was up there and wasn’t moving. A wind came up, from the southwest; the top of the tree swayed; we were ready. Then in the sky appeared a hot-air balloon. Some English balloonists were making experiments with flight in a hot-air balloon along the coast. It was a beautiful balloon, decorated with fringes and flounces and bows, with a wicker basket hanging from it, and inside two officers with gold epaulettes and pointed cocked hats looked through a telescope at the countryside below. They aimed the telescope at the square, observing the man in the tree, the stretched sheet, the crowd, strange aspects of the world. Cosimo, too, had raised his head, and looked attentively at the balloon. When, look, the hot-air balloon was seized by a gust of the southwest wind; it began to run in the wind, spinning like a top and heading toward the sea. The balloonists, without losing heart, were working to reduce—I think—the pressure of the balloon and at the same time rolled down the anchor, seeking to hook it onto some support. The anchor flew silver in the sky, hanging on a long rope, and obliquely following the course of the balloon it passed over the square, nearly at the height of the top of the walnut, so that we were afraid it would hit Cosimo. But we couldn’t suppose what in an instant our eyes would see. The dying Cosimo, at the moment when the rope of the anchor passed by him, made one of those leaps that were usual with him in his youth, grabbed the rope, with his feet on the anchor and his body huddled, and so we saw him fly away, dragged in the wind, barely braking the course of the balloon, and disappear in the direction of the sea . . . Ombrosa is no longer there. Looking at the empty sky, I wonder if it really existed. That ornamentation of branches and leaves, forks, lobes, feathers, minute and without end, and the sky appearing only in irregular flashes and cutouts, maybe existed only because my brother passed there with the light step of a long-tailed tit, was an embroidery, made on nothing, that resembles this thread of ink, as I’ve let it run for pages and pages, full of erasures, of references, of nervous blots, of stains, of gaps, that at times crumbles into large pale grains.